Ongoing chronic pain can lead to poor sleep and concentration, reduced mobility that limits physical activity, and social withdrawal that takes a toll on mental health. When factors that play a role in causing pain are unexplained, pediatric patients may live with unresolved pain and difficulty finding a clear diagnosis — known in medicine as diagnostic uncertainty.

During National Pain Awareness Week, we sat down with two researchers to discuss myofascial dysfunction and pain: Dr. Gillian Lauder — an investigator at BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute (BCCHR), a pediatric anesthesiologist at BC Children’s Hospital (BCCH), and a complex pain physician — along with her clinical research coordinator, Nicholas West.

Myofascial dysfunction is defined as stiffness, contraction, and tethering in the soft tissues of the body, such as the muscles, skin, and fascia (the connective tissue that surrounds and weaves through muscle). This makes it hard for soft tissues to move as they normally would and may lead to chronic pain. Myofascial dysfunction is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

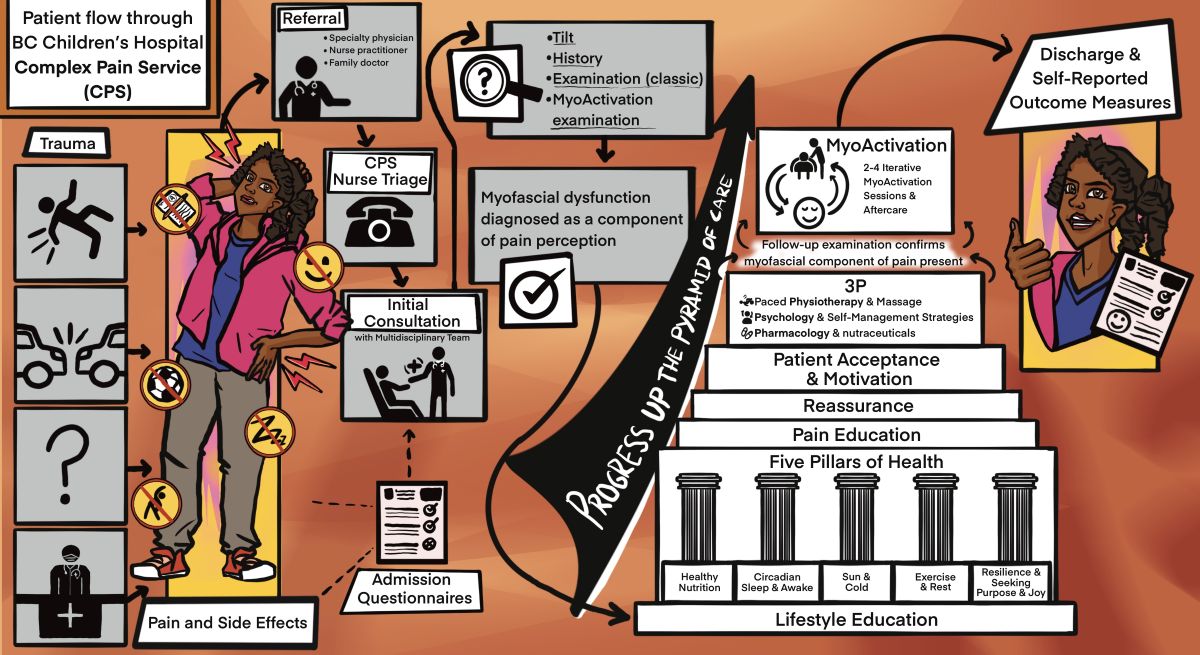

BCCHR researchers are investigating the effectiveness of myoActivation® for pediatric patients with chronic pain. myoActivation is a simple and structured process that helps identify myofascial sources of pain, and provide both diagnostic certainty and a potential targeted therapy, which includes using a needling technique to treat the affected soft tissues. Preliminary findings suggest that this innovative method reduces pain and improves mobility and the sense of well-being. In this Q&A, Dr. Lauder and Nicholas discuss myofascial dysfunction and pain, treatment strategies, and their research.

Why do patients get myofascial dysfunction and pain?

Gillian Lauder: Myofascial dysfunction usually starts in response to trauma, injury, surgery, repetitive strain, poor posture, muscle overuse, or nutritional deficiencies. An injury can cause muscle fibres to contract and get stuck in a shortened state. This spot is called a trigger point and can often be felt as a tender density or knot in the muscle. This tight knot limits blood flow to the muscle, reducing its supply of oxygen and nutrients. Without proper blood flow, waste products build up, which irritates the surrounding pain receptors. Because all the muscles and organs are connected by fascia, a trigger point in one area can cause pain in a distant spot. After an injury, the fascial tissues can thicken, become tender, and lose some of their flexibility. Scars also play an important role in pain and movement. During healing, the soft tissues around a scar can stick together, creating tension that spreads into deeper layers and muscles. When scars, tight fascia, and muscle trigger points combine, they can increase pain and stiffness and limit movement.

Inadequate pain management may result in increased pain or fear of movements, decline in physical fitness, emotional distress, mood issues, and general mistrust in the medical system. When pain persists, it often becomes the main focus — and what we focus on tends to become amplified. Pain perception is complex and specific to each individual. We describe it to young people in the clinic by using pizza as an analogy. There are many different slices that impact the final pain message in the brain. Some are related to biological factors, of which myofascial dysfunction is one tiny slice. We start treatment with the 3P approach, involving physiotherapy and massage, psychology, and pharmacology to address all the slices of the pizza.

Can you talk more about how myofascial dysfunction is diagnosed?

GL: Myofascial dysfunction can be diagnosed based on the patient’s history and myofascial examination. No fancy investigation is needed. Their history of physical traumas, surgeries, and scars as far back as they can remember help to give clues about where the soft tissues may be impacted. Examination is quite different compared to a classic medical examination. It focuses on posture, movement tests, and inspection of the skin for asymmetries and scars, followed by careful palpation of the muscles and fascia to find painful trigger points.

What are the treatment strategies when myofascial dysfunction is present in chronic pain?

GL: In the Complex Pain Service at BCCH, we provide assessment and care to pediatric patients impacted by chronic and complex pain. We use an interdisciplinary standard-of-care approach, which is more effective than single-discipline treatments. Regardless of the characteristics of the pain, the initial treatment includes the 3P approach we mentioned earlier. When diagnosed with myofascial dysfunction, patients start supplementation and massage therapy as well to help reduce muscle tension.

Since pain perception is complex, we also need to address other factors that are playing a role. Some selected patients are eligible for myoActivation, which was developed by Dr. Greg Siren, a family physician who helped us bring this approach to BCCH. Since 2017, we’ve been using it as an additional tool for interdisciplinary care. Patients of any age with chronic pain can benefit from this approach because we work on preventing procedural pain with topical anesthetics and, if necessary, sedation.

What is the relevance of the myoActivation research?

Nicholas West: We have objective evidence associating myofascial dysfunction to movement restriction, and myoActivation to improvements in range of motion and ease of movement. These findings support a key concept to understanding the relationship between immobility and pain: the body is a “biotensegral” structure. This means it’s like a suspension bridge where support is provided by our bones and joints, and our soft tissues work as cables allowing the body to bend or twist without falling over and, later, return to its original position.

GL: This research is beginning to provide evidence for clinicians to think about examining pediatric patients differently so that the myofascial component of pain and mobility impairment can be recognized. An early diagnosis prevents a downward spiral and has a positive impact on patients’ well-being. If we can resolve the pain in primary care settings, we may also reduce the need for multiple investigations, emergency room visits, and unnecessary specialty referrals.

What’s next in terms of research?

GL: All the studies involving myoActivation in pediatric patients so far have been conducted in BC, mostly at BCCHR. We’ve seen immediate changes in how a patient’s body moves after this treatment. Our research suggests that it helps release tension in the underlying soft tissues, but there are still many questions to be answered. We’re in the early stages, so more research is required to establish robust evidence of the efficacy of myoActivation. We also need to partner with other centres to support larger clinical trials.

NW: A better understanding and wider application of myoActivation could have a massive impact on early and effective treatments to address mobility impairment and pain. Continuing this research can provide us with answers that potentially change how classic medicine treats patients with chronic pain.

What advice can you give to families whose children have undiagnosed pain?

GL: A child or youth who has had pain for a long time may have underlying factors that must be addressed. It’s important for families to understand the different types of pain and advocate for help through primary care or their pediatrician. We’ll continue to explore the many questions that need to be answered through our research in the hope that fewer children and youth develop chronic pain.

More resources:

Support — Anatomic Medicine Foundation

myoActivation: A structured process for chronic pain resolution

Early-life trauma as a trigger for developmental myofascial dysfunction: A case report