Adya experienced her bleakest moments in Grade 9, back in February 2021.

She’d been called lazy and weak in front of 30 of her peers, and the depression that had overtaken her since the start of the school year during the COVID-19 pandemic — with its social isolation — deepened.

“I’d take a paper clip and stab it into my finger just to feel something,” the now Grade 11 student says.

She had been a high achiever who was active in sports and air cadets and had awards for academics, integrity and public speaking. Now she found herself self-harming and wondering if anyone would miss her if she were dead.

Adya was one of dozens of teens who contributed to a new report released today, entitled Improving Youth Mental Health and Well-being During the COVID-19 Recovery Phase in BC, which identifies strategies to support youth mental health and well-being during the pandemic recovery period.

She’s a member of the Youth Advisory Council for the Youth Development Instrument (YDI), an annual self-report questionnaire designed to learn about the social and emotional development, health and well-being of young people 15 to 17 years of age in B.C. Like other YDI ambassadors, Adya is passionate about improving youth mental health and shares her experience in an effort to help others.

If you or a loved one is struggling,

24-hour mental health supports are available through:

• Kids Help Phone text message service 686868

• The Crisis Centre of BC 1-800-784-2433

Coordination is key

Dr. Hasina Samji is the lead author of the report and co-principal investigator of the Improving Child and Youth Well-Being project with Dr. Evelyn Stewart, an investigator and director of research for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at BC Children’s Hospital. Dr. Samji says mental health education and proactive approaches to preventing mental illness need to be better coordinated in B.C.

“We know that we have not been able to move the needle on youth mental health over the last decade, even pre-pandemic,”

says Dr. Samji, an affiliate investigator with BC Children’s Hospital, a senior scientist in Population Mental Well-being at the BC Centre for Disease Control and an assistant professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University.

Despite many different youth mental health promotion initiatives, there’s an urgent need for disparate programs to be better coordinated so that funding and resources can be better directed to help schools, provincial government, non-profits and other groups ensure no child falls between the gaps.

“There are lots of great people doing amazing work across sectors, but we really need to step up our efforts to collaborate, integrate and not duplicate,” says Dr. Samji.

She explains that the roles and responsibilities of different partners need to be made clear to all who work in this realm, along with how they can better integrate and work with the best available evidence.

“Do we need to establish a coordinating body to manage the collection of best practices, evidence and data on young people’s well-being that could better support the education system?”

The Improving Youth Mental Health and Well-being During the COVID-19 Recovery Phase in BC report promotes three priority recommendations: serve underserved populations better, improve collaboration among mental health partners, and enhance social and emotional learning strategies in schools and community settings.

These recommendations are based on scientific literature, data, interviews with youth and two deliberative dialogues with key stakeholders that considered modifiable factors and successful coping strategies. Representatives of four provincial ministries, education, health, the non-profit sector, parents and dozens of young people, including Adya, were involved in the conversations. Participants in the first deliberative dialogue shared effective strategies for addressing youth mental health and barriers to implementing them. At the second deliberative dialogue, participants solidified the three priority recommendations and conceptualized the related action steps that would be needed.

“There was such great energy in the room,” says Dr. Samji about the first dialogue, where they brainstormed best practices and strategies to promote youth mental health during the pandemic and through the recovery phase. “There was a sense of optimism and gratitude for the energy and commitment that so many provincial partners are bringing to the table to innovate and collaborate on ways to improve young people’s mental health and well-being.”

Prioritizing support to underserved populations

Data from Dr. Stewart and Samji’s Personal Impacts of COVID-19 Survey and Dr. Samji’s Youth Development Instrument survey informed the report.

Their studies, combined with the work of other researchers, found that girls, sexual and gender minorities, racialized minorities, Indigenous youth, young people from low-income households and teens with poorer pre-COVID mental health experienced disproportionately deteriorating well-being during the pandemic.

“Youth and their parents repeatedly told us about challenges in accessing mental health support when they needed it,” says Dr. Stewart. "It’s unfortunate that those who were vulnerable beforehand were particularly affected during the pandemic.”

Dr. Samji says specific approaches are needed to effectively meet the needs of particular populations.

“We really need to think about targeted and tailored strategies to support those groups.”

Enhancing social and emotional learning strategies

Attendees at the first deliberative dialogue suggested increasing the incorporation of social-emotional learning (SEL) — the process of developing self-awareness, self-control, and interpersonal skills — into school curricula. These skills are vital for school, work and good mental health. While SEL has been embedded in curricula, uptake differs across schools and districts.

The recommendations include standardizing and enhancing SEL in schools with multi-year, dedicated funding; formalizing SEL positions/champions in schools; collecting SEL data for program evaluation, inter-district sharing of best practices and monitoring; and incorporating SEL beyond schools to pre-school, after-school care and families, perhaps with well-being checks or an app.

“We know it takes a village to raise children, and we know, as well, that schools are so overburdened,” says Dr. Samji. “We need to consider how the broader community can better support staff and student well-being.”

Extracurricular activities, physical activity and getting outdoors

The report includes 10 other recommendations in addition to the top three priorities.

Dr. Samji particularly favours the suggestion that extracurriculars should be reframed as central to youth, family and community well-being, and made more accessible to all.

She also likes the recommendation that more time outdoors should be incorporated into school curricula.

“When we asked young people about their coping mechanisms to deal with distressing events, they highlighted time outdoors and physical activity as two of their most important coping mechanisms,” she says.

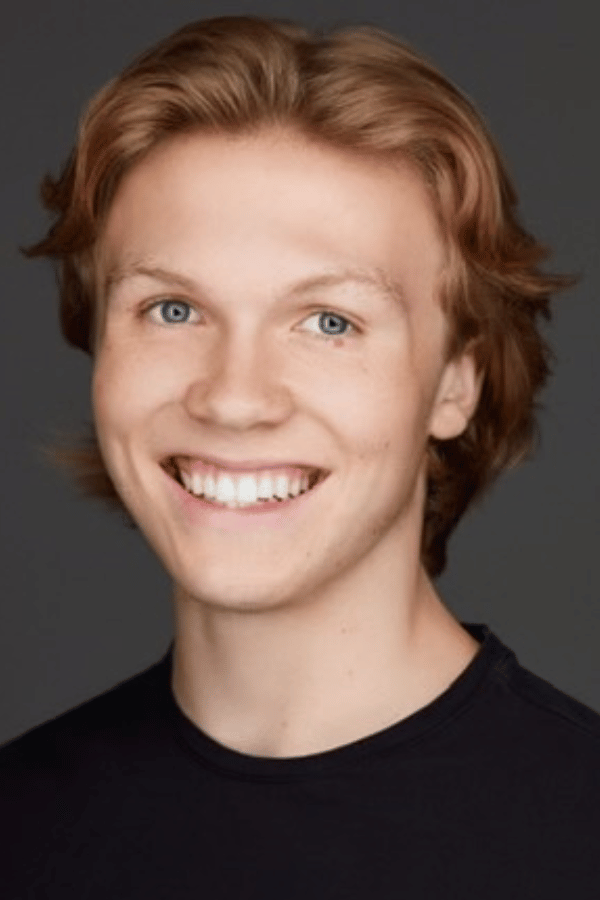

Former Youth Advisory Council member Ayden learned how dismal life can be when he was no longer able to play basketball seven days a week during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While he had struggled with mental health difficulties since elementary school, life pre-pandemic had felt pretty good.

“The first week or two of the pandemic wasn’t bad because I thought it would be a brief lockdown,” the now 19-year-old says. “But once it carried on, it got very taxing on mental health. It took away social interaction. It took away actually physically going to school. It definitely was hard for depression because you’re alone a lot. You’re not able to play sports. You’re not able to hang out with friends.

It was really, really hard to be alone and stuck.”

Silver linings and optimism

Dr. Samji hopes we can collectively learn from such challenges.

“One of the silver linings of the pandemic has been renewed energy and focus on young people’s mental health,” she says.

“It really feels like the perfect window not only to have these conversations, but also to act on some of the findings and collaborate on how to go from data to action.”

“There is so much we can do,” she adds.

“Research shows positive long-term impacts of mental health literacy across lifetimes. Such programs lead to substantial savings for our health system.

It’s important that we recognize that young people become adults who then use our health-care, education, social welfare and justice systems, and if we can prevent the onset of mental illness and contribute to better health and well-being — why not?”

As for Adya, she eventually found a counsellor with whom she felt a connection. She continues to work on her mental health and feels strong enough to share her personal story with the hope that it will help other teens feel less alone.

“I want this report to actually make a difference,” she says.